Yoko Ono met John Lennon in Barry Miles and John Dunbar’s Indica bookshop and gallery, a veritable hub of burgeoning counterculture in the ‘60s.

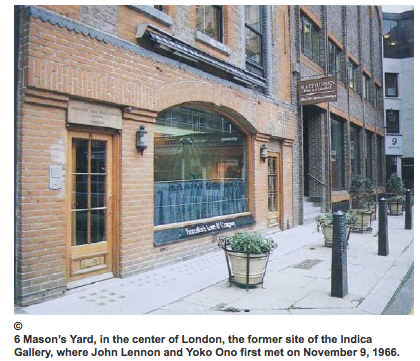

The Indica Gallery is best known for being where Yoko Ono first met John Lennon, which was on Nov. 7, 1966, when we were still hanging the show in preparation for the opening of Yoko at Indica, the next day. The gallery was at 6 Mason’s Yard off Duke Street Saint James’s; the yard is now home to the White Cube gallery. Originally the bookshop was on the ground floor, but by this time it had moved to new premises at 102 Southampton Road. John Lennon often dropped by to visit with John Dunbar, the director of the gallery, and it was accidental that John and Yoko met on this occasion rather than at the opening.

The Indica Gallery is best known for being where Yoko Ono first met John Lennon, which was on Nov. 7, 1966, when we were still hanging the show in preparation for the opening of Yoko at Indica, the next day. The gallery was at 6 Mason’s Yard off Duke Street Saint James’s; the yard is now home to the White Cube gallery. Originally the bookshop was on the ground floor, but by this time it had moved to new premises at 102 Southampton Road. John Lennon often dropped by to visit with John Dunbar, the director of the gallery, and it was accidental that John and Yoko met on this occasion rather than at the opening.

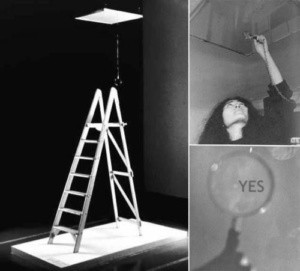

Lennon particularly liked Yoko’s Ceiling Painting. The work appeared to be a blank canvas flat on the ceiling with just one word written on it in tiny letters. Lennon climbed a step-ladder, and balancing at the top, peered through his little round glasses, and through a larger round magnifying glass that was hanging on a chain next to the canvas, to look at the word. John said, “I went up the ladder and I got the spyglass and there was tiny writing there. . . and you look through and it just says ‘YES’.”

Lennon particularly liked Yoko’s Ceiling Painting. The work appeared to be a blank canvas flat on the ceiling with just one word written on it in tiny letters. Lennon climbed a step-ladder, and balancing at the top, peered through his little round glasses, and through a larger round magnifying glass that was hanging on a chain next to the canvas, to look at the word. John said, “I went up the ladder and I got the spyglass and there was tiny writing there. . . and you look through and it just says ‘YES’.”

The most popular piece in the show was Yoko’s all white chess set: all the pieces and all the squares were white and the board sat on a white table with two white chairs. Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski visited the show several times late at night, spending hours playing with the chess set until they could no longer keep all the pieces in their minds and had to abandon their game. They never bought the piece.

The most popular piece in the show was Yoko’s all white chess set: all the pieces and all the squares were white and the board sat on a white table with two white chairs. Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski visited the show several times late at night, spending hours playing with the chess set until they could no longer keep all the pieces in their minds and had to abandon their game. They never bought the piece.

In the mid-‘60s, Op Art was very popular: it went well with Vidal Sassoon Mary Quant haircuts, André Courrèges dresses and the dotty Heals shower curtains that Damien Hirst so clearly grew up with.

In the mid-‘60s, Op Art was very popular: it went well with Vidal Sassoon Mary Quant haircuts, André Courrèges dresses and the dotty Heals shower curtains that Damien Hirst so clearly grew up with.

At first the only gallery to feature Op Art work in London was Signals, but when the Indica Gallery started up in the autumn of 1965, it also featured the work of kinetic artists. When Signals closed in October 1966, Indica Gallery took up many of their artists. Indica’s first proper show, opening June 4, 1966, was the Groupe de Recherche de l’Art Visuel, (GRAV) a loose collective of kinetic artists. John Dunbar drove to Italy to represent the gallery at the XXXIII Venice Biennial. He was on his way back to London when the news came through on the car radio that the Argentinean Julio Le Parc, the co-founder of GRAV, had been awarded the International Painting Grand Prix. Julio was reported to have fainted when he heard the news. Indica was showing the winner of the most prestigious art prize in the world in its first show.

The Americans had wanted Robert Rauschenberg to win, but were quite prepared to buy the work of whoever won. At that time the bookshop, which I ran, was still on the ground floor. On John’s first day back we were standing in the bookshop when a large man in an eye-catching tartan jacket burst in the door. Identifying us the proprietors he announced, “I’m a big American collector! Lemme see your Le Parcs!”

John polished his granny glasses, “I’m a little English art dealer,” he said. “And the Le Parcs are all downstairs.” The American bought the biggest that we had. It was only later that we found out that the price list given us by Le Parc was a joke. He had not expected us to sell anything — to him it was just a friendly, sympathetic bohemian establishment — and had put random prices down, ranging from ten pounds to thousands. John quickly contacted Le Parc’s Parisian gallerist Denise René for a more accurate list and renegotiated with the Big American Collector.

The GRAV show was very popular and received a lot of press: it was more like a fairground sideshow than a conventional art show.

One of Julio’s pieces was Passage Accidenté, a set of eight square black wooden boxes, about ten inches deep, arranged like large stepping stones outside the gallery. Each had a projecting piece of wood on the bottom, like the keel of a boat, to make it unstable so that they tipped and moved as you walked over them. Children loved them, and quite a few adults enjoyed playing on them too. One lunchtime we set off for the café to find that they had disappeared — the dustmen had assumed they were rubbish and thrown them on the back of their cart. John ran to the phone but by the time we located them they were on a refuse barge heading down the Thames.

The London evening papers had a wonderful time reporting how works by that year’s biennael winner had been mistaken for rubbish. Fortunately Julio found it amusing.

Barry Miles, It Looked Like a Load of Rubbish To Me, is excerpted from Laura K. Jones, ed., A Hedonist’s Guide to Art, 2010, published by Hg2, a publisher of luxury city guides.